Motivation

One of the big “WTF” hurdles for apprentice JavaScript developers, that come from languages that mostly embrace synchronous and blocking IO APIs like Java or PHP is to get into thinking asynchronously about everything IO related in JavaScript with its event loop construct.

It is actually one of the cool things about JavaScript and why NodeJS on the server got so much attention in the beginning, so it is something anyone at least half serious about learning JS should learn about.

What does asynchronous vs synchronous IO actually mean?

For any computer program to do something useful it is important to handle Input/Output (IO) operations.

IO is basically everything that gets in and out of the “container” your program runs in, like mouse or keyboard input, sending a request and receiving a response from a web service or reading a file from disk.

To handle this there are two different API models, one is synchronous and blocking, the other is asynchronous and non-blocking.

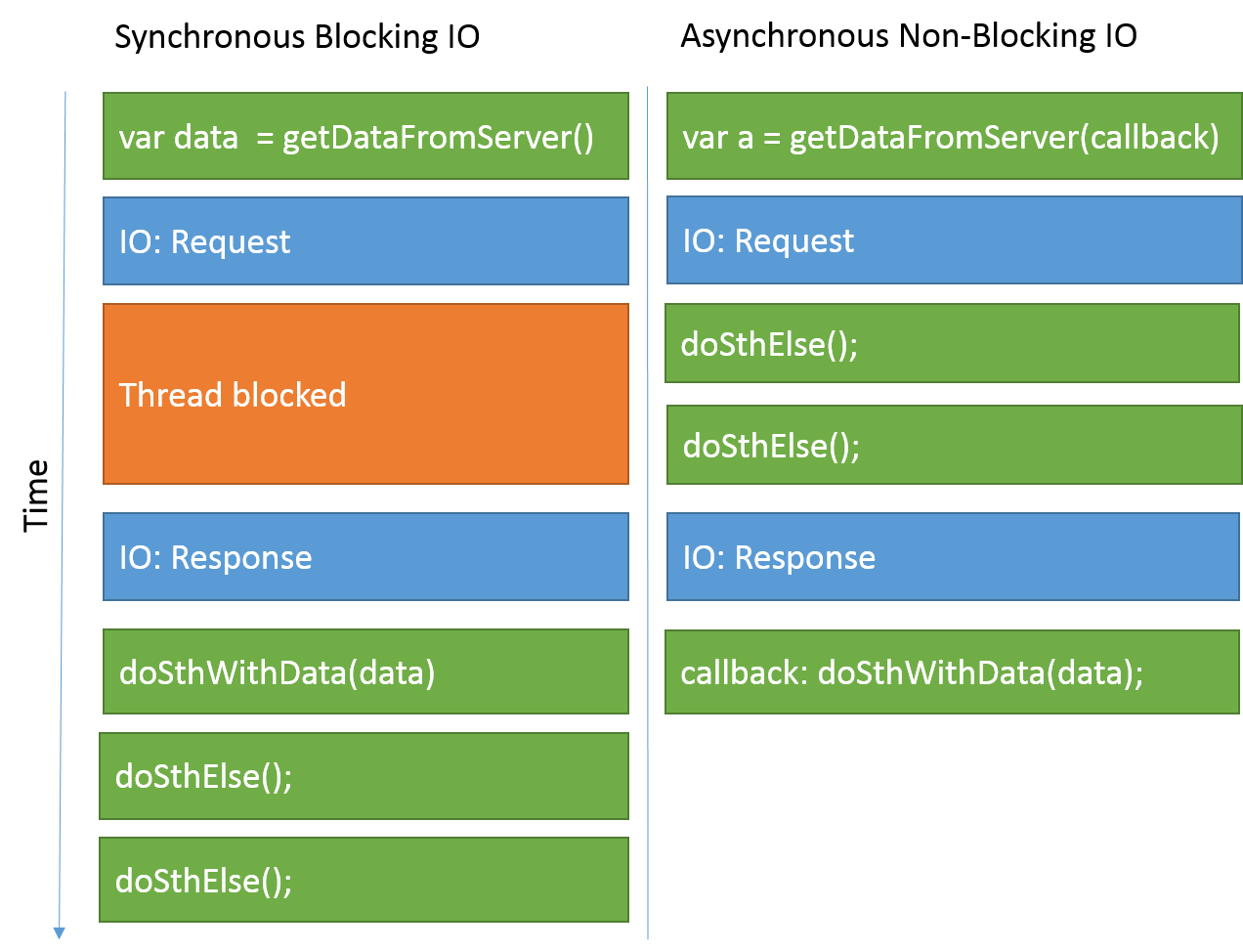

The illustration explains the basic difference between the two approaches.

The blocking IO approach on the left ‘waits’ for the response to come back until the program continues. The asynchronous program on the right however continues immediately and invokes a callback once the response came back.

From Callbacks to Generators

While handling blocking IO is pretty straight forward and intuitive, non-blocking IO can be confusing at first. The next part of this article gives concrete code samples of different ways of doing ajax calls in JavaScript synchronously and asynchronously. The examples make use of the jQuery library.

Synchronous/Blocking IO

The XMLHttpRequest API actually allows you to do ajax calls synchronously.

This is however almost never a good idea. Due to the single threaded nature of JavaScript your complete UI will be blocked while you do your call. It is even flagged as deprecated by recent Chrome versions

$.ajax({

url: 'doSth',

async: false,

complete: function(data){

console.log('First');

}

});

console.log('Second');

Pros

- People are often more used to blocking IO APIs

Cons

- You block the UI thread

- Bad user experience, as your complete UI hangs during the request

Callback Functions: The basis of non-blocking IO

This is the way the browser JS APIs such as DOM handlers are implemented at base. You register callback functions, that get called by the browser once the IO operations returns.

To use this approach directly however may lead to pretty ugly code. Novice programmers tend to build endless ‘callbacks inside callbacks inside callbacks’ chains, which are very hard to read, maintain and debug.

$.ajax({

url: 'doSth',

success: function(data){

console.log('Second');

$.ajax({

url: 'doSthElse',

success: function(data){

console.log('Third');

},

error: function(err){

console.error(err);

}

});

}

});

console.log("First");

Pros

- Asynchronouse IO gives the UI room to breathe

Cons

- Code can get really ugly with endless callback inside callback chains

Promise objects: The ‘State of the Art’ in non-blocking IO

As a way to solve the ‘callback hell’ problem a design pattern called promises (jQuery also calls it Deferreds) got very widely adopted and integrated by popular frameworks.

When using promises you write your asynchronous function calls not by passing in a callback function, but by directly returning a so called Promise object.

As the name implicates this object ‘promises’ you a value.

The promise object is now the place where you can attach your callback functions. This makes it easier to chain asynchronous calls, while staying on the same nesting level.

var promise = $.ajax({url: 'doSth'});

promise.then(function(data){

console.log('Second');

return $.ajax({url: 'doSthElse'});

}).then(function(data){

console.log('Third');

},function(err){

console.error(err);

});

console.log('First');

Notice the callbacks get registered via the ‘then’ function on the promise object.

Pros

- Asynchronouse IO gives the UI room to breathe

- You can write much nicer code, than with pure callback functions

- The pattern got adopted by many libraries and frameworks

- The pattern will be a native part of JS with ECMAScript 6

Cons

- It is a relatively advanced concept for beginners to grasp for solving the simple problem of just chaining two async calls.

ECMAScript 6 Generators: The future of non-blocking IO?

ECMAScript 6 will introduce Generator functions to JavaScript. Generators are a programming construct that basically enable a way of doing iterations.

These iterator functions can be used to create synchronously looking code, that actually gets executed asynchronously in the background. A great blog post, that describes in detail how this will work in detail can be found on the website of Strongloop.

run(function*(){

try {

var result = yield makeFirstAsyncCall();

var finalResult = yield makeSecondAsyncCall(result);

catch (e) {

console.error(e);

}

});

The final code will look something like this. Notice the “function*” keyword, that marks a generator function and the “yield” keyword that marks the iteration steps inside the generator.

It will also be possible to do seemingly synchronous error handling with try/catch in this construct, without an extra fail or error callback as with the other async methods.

You can already play around with all the ECMAScript 6 goodness by using NodeJS 0.11.2+ with the –harmony flag.

Pros

- Straight forward syntax, that looks just like a blocking API.

- Still calls are really asynchronous, so the UI thread can breathe.

- Enables programmers to easily write async code, without necessarily needing to understand it.

Cons

- Only available in ECMAScript 6 (Scheduled for mid 2015 release according to Wikipedia)

Conclusion

In retrospect really understanding asynchronicity and the event loop construct is one of the great things I took from learning JavaScript.

Besides the obvious benefit of writing better JavaScript applications, it opened my mind in thinking about other languages and frameworks too.

For example it recently helped me a lot grasping the concepts behind Akka, which is a framework written in Scala, that implements the actor model for distributed and concurrent computing.